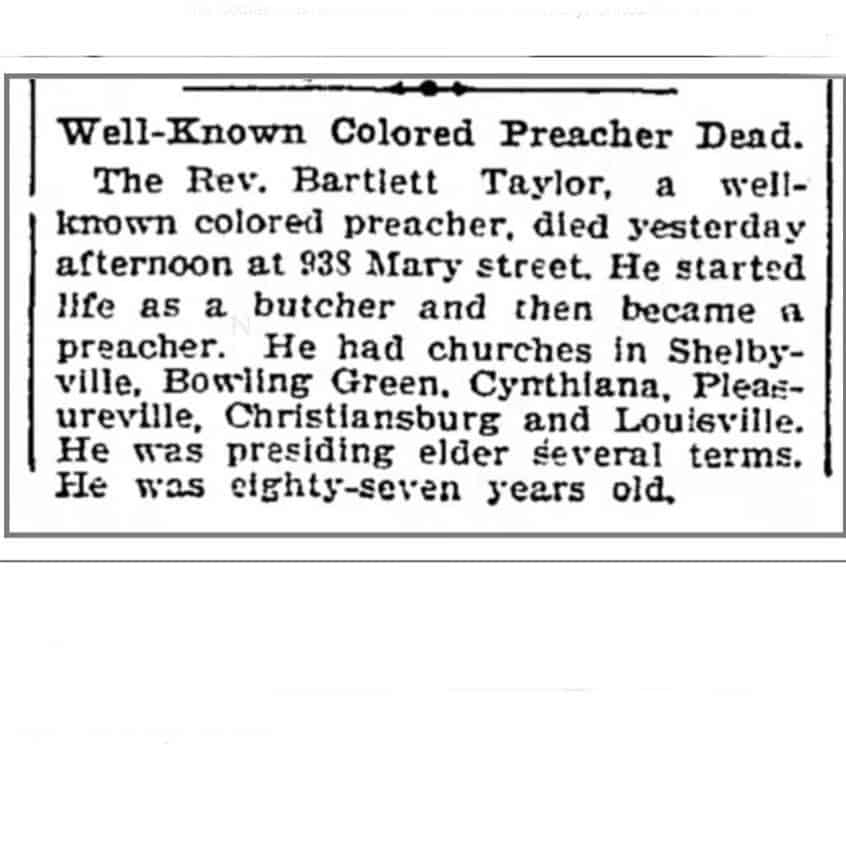

Rev. Bartlett Taylor (1815-1901) was born into slavery in Henderson, Kentucky. His father, Jonathan Taylor, owned Bartlett, his mother, and his siblings. Jonathan Taylor sold many of them to pay for his debts and moved the remaining slaves, including Bartlett, to LaGrange. Bartlett Taylor worked as a butcher to buy his freedom in 1840. He grew his business into a retail and wholesale butcher that also packaged and shipped meat as well as traded livestock. As a fairly wealthy man, Taylor owned several homes and lots on E. Market Street and lived in Germantown at 940 Mary Street (formerly 938). Taylor was also known as a preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. He was a driving force in building AME churches and schools across the state. Image is from “Courier-Journal” article from July 4, 1901.